Children ask a lot of questions in school, but there’s one question in particular that’s the bane of every school teacher’s existence. We’ve all heard it before, whether from friends or from deep down in our own frustrated minds: “I’m never going to use [insert extremely difficult subject here] in real life, so why do I have to learn it?” But perhaps the question everyone should be asking is: “I’m never going to remember all of this in 20 years, so why bother learning it?”

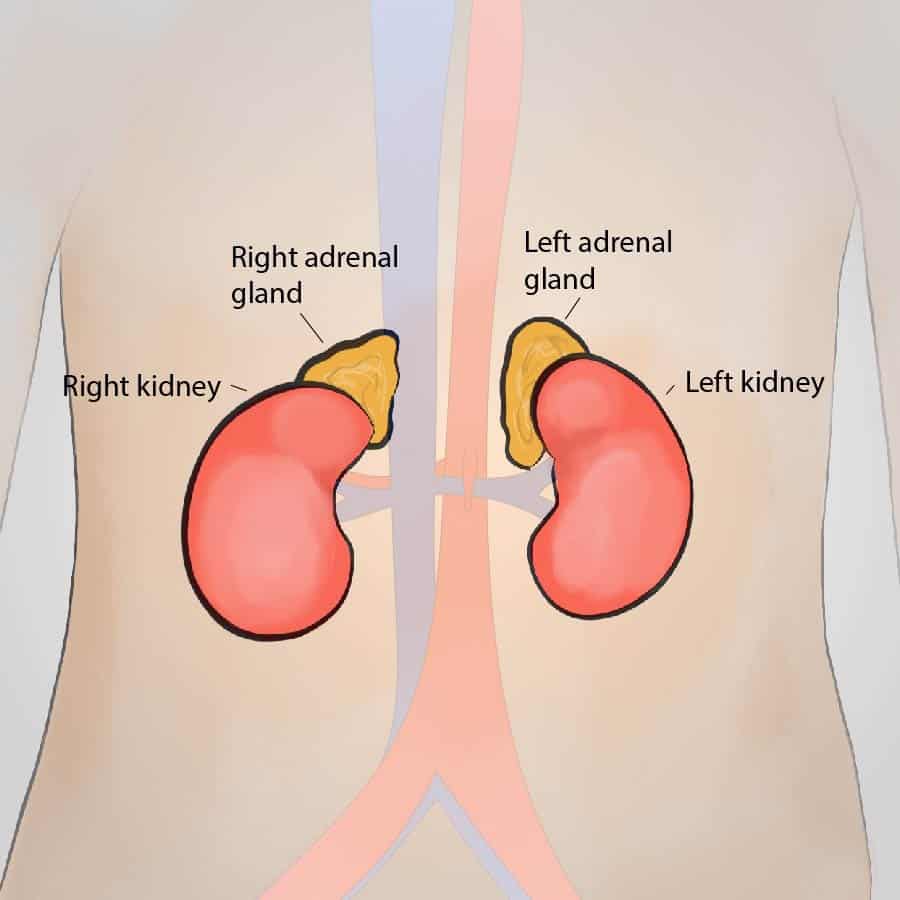

It’s true that over the course of a typical school career, students learn so much that it’s inevitable much of the information will be gone by the time they graduate college. Case in point: How many of these 25 vital body parts can you locate? Scientists at Lancaster University created the world’s largest anatomy quiz after discovering only 15 percent of adults can properly locate their adrenal glands (you can stop looking now; they’re above your kidneys).

According to the university’s previous research, people are most likely to know where major body parts like the brain, cornea, and muscles are found. They’re much fuzzier when it comes to locating organs like the spleen and pancreas. Most of this information is basic middle school Biology, so why can’t many adults remember what should be simple information? For that matter, why is it so difficult for them to remember the title of a book?

How fast do students forget what they learn?

Memory is an odd thing. For years, neurobiologists have focused on studying how we remember things. But more recent studies have focused on the process of forgetting, also called “transience,” and suggested that we forget things in order to ease decision-making, especially in difficult situations. Seen this way, memory is less about “what you retain versus what you forget” than it is an evolutionary system for good decision-making. You forget what you don’t need and remember what you do.

Somehow I can recite lines from movies and tv shows but cant for the life of me remember anything school related

— Eva (@EvaMcCoolGug) April 12, 2017

But just how much does the average person retain what they’ve learned? Donald Bacon, PhD, is a professor in the department of marketing at the University of Denver, where he specializes in marketing education and serves as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Marketing Education, the top journal in its field. “When I started teaching, I discovered that we know a lot more about marketing than we do about marketing education,” he says.

“When I got my PhD, and this is still true at many schools, I was expected to teach for the rest of my life, but I had no formal training in teaching or education. Fortunately, many of the methods of statistical analysis that I learned in my program could readily be applied to the problem of understanding how marketing students learn, so I have had a lot of fun working on studies in marketing education.”

In 2006, Bacon and a colleague, Kim Stewart, released a longitudinal study titled “How Fast Do Students Forget What They Learn in Consumer Behavior?” In it, they tracked individual students from 8 to 101 weeks after a course to test how much knowledge from a class on Consumer Behavior they retained.

“After I had been teaching one particular marketing course for several years (Consumer Behavior), I became concerned that students may not recall the information they were learning for very long,” Bacon says. “Fortunately, I had saved student final exam scores from every course I taught.” Bacon gained permission from several colleagues to test some of his former students who were taking a different class later in the program.

“There, I asked the students to take a subset of my final exam again and to give me permission to use their data,” he says. “We got over 90 students to give us final exam and post-final exam data. Kim Stewart and I then analyzed the data using Rasch measurement, so that we could place all of the students, no matter which version of the exam they took, on the same ‘knowledge scale.’”

I cant remember anything Ive learned so far in college but get this, I just read a term in my marketing textbook called “Selective Retention” meaning we remember only what we want to remember so that explains a lot lol

— meg (@megaanblair) February 20, 2018

Bacon and Stewart tested some students who had taken the final exam just a few weeks earlier as well as some who had taken the exam several years prior.

“From there, it was not hard. Use statistical analysis to determine how fast the students were forgetting the material,” Bacon says. “That’s how we estimated that most students forget what they had learned in about two years. Our findings are somewhat consistent with an earlier study by Harry Bahrick (1984) that looked at how well Spanish is remembered after graduation.”

In that study, Bahrick found that over a 50-year period, the amount of Spanish retained depends on how well the material was originally learned, as well as how often it was rehearsed over time. Students who stopped speaking, writing, or listening to Spanish forgot the language much more quickly than those who continued to rehearse it.

Curiously, the study concluded that, depending on how it was originally learned, large swaths of information can remain in a person’s memory for over 50 years, regardless of how often it’s recalled or rehearsed. In addition to Spanish, this may include the names or faces of friends you had in elementary school that you haven’t spoken to in years. Bahrick dubbed this extremely long-lasting memory “permastore.”

But permastore doesn’t retain everything, and most of the things you learned about in school will be forgotten in a few years. “I was a bit surprised by how quickly students forgot what they had learned in marketing,” Bacon says. “I knew they forgot a lot, but forgetting most within a couple years was disappointing. Disappointing, but also fascinating and enlightening.”

Bacon uses a common teaching analogy to explain the ramifications of his findings. “I think a lot of faculty implicitly assume that teaching is like pouring knowledge into an empty vessel and filling it up,” he says. “What teachers don’t recognize is that the vessel has holes in it, and knowledge is leaking out at such a rate that not much will be left a few years after graduation.”

So why learn anything at all?

If everything you learn will just be gone in two years, why bother learning it at all? The answer, as Bacon points out, is that there are many benefits to learning new things that reach beyond how much of it you retain.

“First, we know that people can relearn content much more quickly than they learned it the first time,” he says. “Thus, although some knowledge seems to be forgotten, there are some subtle traces left in the brain that can be called on later to relearn the material if needed.”

There are also things that people can do to improve memory.

“‘Distributed study’ is one approach that is widely studied and was supported again in our study,” Bacon says. “Distributed study means studying something several times over a period of time. It’s the opposite of cramming, where a student might try to memorize all of the content in one sitting, the night before the exam. Going a step further, when students learn the same content across several courses, perhaps with different examples, we would expect them to be able to retain that content much longer. Bahrick found that Spanish majors, who obviously must have memorized some of the same Spanish words and grammar rules over several years in college, retained some Spanish knowledge for decades.”

But beyond simply improving your retention ability, school gives you skills that go deeper than just what you know. “Another reason to study hard is that college education appears to change students in more ways than just filling their heads with knowledge,” Bacon says. “Over many semesters, students must dig into new readings, deeply analyze new phenomena, and form new understandings of complex material. Thus, these particular skills are rehearsed several times in the course of a college career. These skills are related to the development of critical thinking. It is these skills that may be very valuable to employers, and because of the ‘distributed study’ of these skills over many years, these are likely to be retained.”

“College may be somewhat like aerobic exercise,” Bacon adds. “It doesn’t matter too much exactly which exercise you choose—walking, running, swimming, a rowing machine, whatever—as long as you get your blood pumping, you’re improving your overall fitness. Similarly, in college, the specific content may not matter that much for many students; it is the act of building mental fitness, or developing powerful new mental habits, that may provide benefits to students for the rest of their lives.”

In order to get the most out of school, Bacon advocates for students majoring in a subject they are passionate about. “They may forget much of the specific content, but if they have the motivation to really dig deep in whatever area, they can build skills that will help them in many different occupations after their college days are over,” he says. “In fitness, many experts recommend picking whatever exercise that you think you can stick with. In education, I recommend that students pick an area of study where they really want to work hard and learn.”

I hate to side with the seventeen-year-old version of myself, but I have never needed to use algebra as an adult.

— Jonah Bayer (@jonahmbayer) February 18, 2011

Even if your college days are over, the principle remains the same. You are more likely to remember the things you are most interested in. So don’t despair over what you might forget. Focus instead on the benefits that learning provides—the skills that will last long after the information itself might be gone.